Proofs

The proof building skills you gain from this class will be foundational for your success in CSE 102. They may look intimidating but the most comforting advice I have received from my teachers and tutors is that notation is half the problem. Once you work your way through the notations in the problem, you can start to understand what you are looking at and think of approaches to solutions. The following are just previews into common proof techniques from CSE 16 and 102.

Note: Sometimes professors say which proof technique to use and sometimes it’s not explicitly stated, so you will need to pick a valid proof technique that can get you the desired result. So these are just good skills to keep in mind when creating a proof. Don’t worry - proof get a little easier and make more sense with practice!

Contradiction

The starting point for a proof by contradiction can be a little tricky, but it is fun when you get the hang of it. A common set up is simply “prove this” and it gives you some expression to prove. The way a proof by contradiction works is that you take the negation of what was given and assme those are True as your “givens” to start with, then you continue using those negated expressions to see if you derive a contradiction (or something that cannot possibly be True). I will give and explain one example below.

Example

Prove the $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational.

The first thing to do in a proof by contraction is to negate what is given and then assume that as a hypothesis.

We assume $\sqrt{2}$ is rational and use various mathematical definitions to try to find a contradiction. The idea here is that we have to explore the world to see what would happen if $\sqrt{2}$ is indeed rational and look for something that doesn’t make sense. In this problem, we will see that the greatest common divisor between two number is found to be 1 and not 1 at the same time. This is the contradiction because this cannot be true. So we can conclude the $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational because if was rational then we have shown that a contradiction arises.

Note: $gcd(a, b)$ is the greatest common divisor between $a$ and $b$. In this problem, we will be concerned about $gcd(a, b) = 1$, which means that $\frac{a}{b}$ is in its simplest form and $gcd(a, b) \neq 1$, which means $\frac{a}{b}$ is not in its simplest form.

The proof goes like this:

- Assume $\sqrt{2}$ is rational.

- This means $\sqrt{2}$ made up of some $\frac{a}{b}$ where $a, b \in \mathbb{Z}$ and $b \neq 0$ and $gcd(a, b) = 1$.

- Now, $\sqrt{2} = \frac{a}{b}$.

- Some rearranging gives, $2 = \frac{a^2}{b^2}$.

- Solve for $a^2$ gives $a^2 = 2b^2$.

- Using a theorem that says if $a^2$ then, $a$ is even too (it’s a fun, quick proof to prove this theorem, try it), we can see that 2 divides $a$ evenly because the theorem says $a$ is even, so it’s a multiple of 2.

- Then from $2 = \frac{a^2}{b^2}$, we can solve for $b^2$ to get $b^2 = 2a^2$.

- Same as above, we can see that $b^2$ is even and it follows that $b$ is even.

- Now, we have something that doesn’t make sense. We found that $a$ and $b$ are both even, which means that 2 can divide them both, which means $gcd(a, b) \neq 1$. However, earlier in proof, we stated that the $gcd(a, b)$ is 1. These both cannot be true at the same time, so we can conclude that the $\sqrt{2}$ is irrational because otherwise there would be an inconsistency.

Formal Proof Rules

Before we get to the next techniques, you need to be familiar with what is and how to make a formal proof. In general, these are made with two columns, left side has the mathematical expressions and the work shown and the right side as the name of the rule or explanation of the reasoning that you used to get to that result. A couple rules and then the example to tie it all together:

- Two columns: left has the actual expressions, right has the name of the the rule you applied and the line numbers for the expressions involved.

- Number each line starting from 1.

I know it is annoying to always “show your work”, but it is easy to get lost or make a small mistake in the proof and then the answer is off or you cannot get to the correct answer. There are many ways to make a proof for a given problem, so these rules are in place to make it clear to the reader how you solved it and to yourself to follow your process to easily backtrack if something went wrong. Believe me, it is a time saver.

Contrapositive

The contrapositive is also an interesting proof technique. This technique uses the fact that $p \rightarrow q$ is logically equivalent to (i.e. the same as) $\neg q \rightarrow \neg p$. You can check this equivalence for yourself by applying the Definition of Implication to both statements and seeing that they are the same.

This may seem a bit unusual but it is incredibly useful to be able to rewrite a given problem in different ways and still maintain the same logical value. You can think of this as the same thing as simplifying or factoring an expression in Calculus - you get the same answer, but the manipulation to the expression makes it easier to work with.

Definition of Even and Odd

For the example below and for other proofs you may come across it is good to explicitly know the formal definitions of even and odd numbers.

- Odd: The number can be rewritten in the form of $x = 2m + 1$, where $m \in \mathbb{Z}$. You can try this with any integer for $m$ and see that $x$ will always be odd.

- Even: The number can be rewritten in the form of $x = 2m$, where $m \in \mathbb{Z}$. You can try this with any integer for $m$ and see that $x$ will always be even.

Example

Prove that if $n^2$ is even, then $n$ is even.

If you try to prove this directly, it will be quite difficult. So, we will take the contrapositive and prove it indirectly using the 2 column formal proof layout with the math on the left and the reasoning on the right.

Contrapositive: Prove that if $n$ is odd, then $n^2$ is odd.

| Expressions | Reasoning |

|---|---|

| 1. $n$ is odd | Hypothesis 1 |

| 2. $n = 2p + 1$, where $p \in \mathbb{Z}$ ($p$ is an integer) | Definition of odd |

| 3. $n^2 = (2p + 1)^2$ | Logically/Mathematically equivalent to line 2 |

| 4. $n^2 = 2(2p^2 + 2p) + 1$ | Logically/Mathematically equivalent to line 3 (multiplied the square and factored out 2) |

| 5. $n^2 = 2k + 1$, where $k = 2p^2 + 2p$ and $k \in \mathbb{Z}$ | Logically/Mathematically equivalent to line 4 (defined a new variable $k$ as an integer) |

| 6. $n^2$ is odd | Logically/Mathematically equivalent to line 5 by the definition of odd |

Notice how most of this proof was just applying the formal definition of odd numbers (which you already knew but not formally) and manipulating the expression until something useful came about. There is not too much to explain other than reading the proof and following along because most of it is things you already knew but just slightly more formal!

Rules of Inference

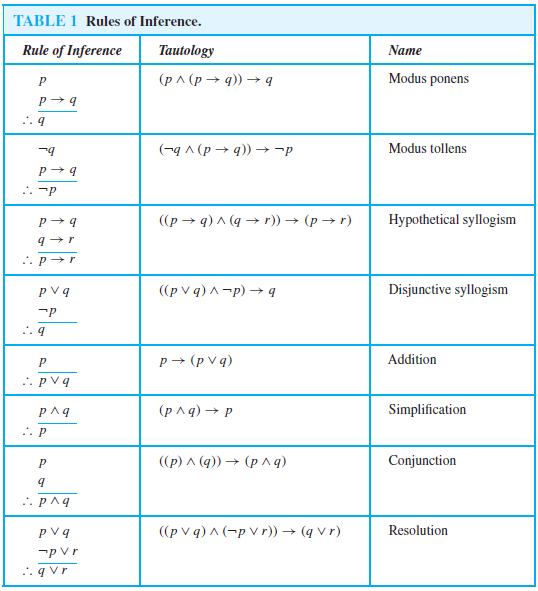

This handout will be your best friend when doing some more formal boolean algebra proofs (see the Proofs section here). Like the previous handout, I will explain one rule from this one so you know how to read and use it when you have a formal proof to solve.

A reference chart for the rules of inference.

Diagram: skedsoft.com

(Click here to download the image if you want to save it for safe keeping.)

Notation in the Rules of Inference

The $\lnot$ symbol is another way is representing a negation/inversion. The $\therefore$ symbol is called “therefore” and means therefore, you can think of it as an equal sign for now. It will make more sense in the example below. That is all the new notation in the handout! The rest should be explained in previous parts of the guide!

Rules of Inference Example

I think the easiest way to understand how to use and read this chart is by making a small proof and walking you through my thought process! I will put the proof up first then explain it under.

Given: $(p \land q) \rightarrow r$, $p \rightarrow p$, $q$. Prove $r$.

| Expressions | Reasoning |

|---|---|

| 1. $(p \land q) \rightarrow r$ | Hypothesis 1 |

| 2. $q \rightarrow p$ | Hypothesis 2 |

| 3. $q$ | Hypothesis 3 |

| 4. $p$ | Modus Ponens, lines 2 and 3 |

| 5. $p \land q$ | Conjunction, lines 3 and 4 |

| 6. $r$ | Modus Ponens, lines 1 and 5 |

You are given three “hypotheses”, which are the expressions that are given to you to use to solve for $r$. You are trying to derive $r$ from these three hypotheses. I like to list out the given hypotheses first, so they are there when I want to use them later, but you can write them down you need them as you go through the proof too.

Now to get to line 4, I look at the rules chart and I see what kind of rules I can apply to any previous lines and see if that gets me anything that can be useful. In this case, I see that Modus Ponens says if you have a line that says $p$ and a line that says $p \rightarrow q$, you can get $q$ as a result. I know the letters are a bit off but that is okay as long as you keep it consistent, you can make a substitution, so you can temporarily think of the $p$ in the proof as the $q$ in the chart and vice versa.

The logic behind Modus Ponens applied to line 4 is that if you have the value of $q$ in line 3 and you have the expression that says $q$ implies the value of $p$, then you can use $q$ you have to get the value of $p$. I think of this one as “unlocking”. I need to get a $q$ because I have something that tells me that $q$ “unlocks” a new value that I need, which is $p$.

Put into a more concrete example, let’s say $q =$ it is raining and $p =$ get an umbrella. Then you have a line that says $q \rightarrow p$ (i.e “if it is raining, then get an umbrella). You can observe that is raining, so we have established $q$ to be True (which is what line 3 represents in the proof). We have a statement (the implication arrow) that says what to do if it is raining, so we can conclude $p$ from that, which is to get an umbrella.

In line 5 of the proof, this is using the Conjunction rule, which allows you to combine any expressions in the proof so far with an AND ($\land$) between them. In this case, I see that it would helpful to do that because Hypothesis 1 on line says that if you have $p \land q$, you can get $r$, which is what we need.

Finally, I apply Modus Ponens again to lines 1 and 5 to get $r$ from $p \land q$ and $(p \land q) \rightarrow r$.

Induction

Induction is usually the proof technique that is hardest to grasp in my experience working with students, but it gets easier with more practice problems.

The easiest introduction to the concept here is to think of a staircase. In order to begin walking on the staircase to get to each next step, you must first get on the very first step, but when you get on the first step, you know know how to get to the next step. So you use that information to get you to each next step until you get to the end.

In inductive proofs, it is a similar flow: the first “step in the stair case” is a mathematical expression that must be established as true. Then you use that proven statement to help you prove each next step.

There are two types of induction: weak and strong.

Weak Induction

Putting the staircase analogy formally, $p(n) \rightarrow p(n+1)$, where $n \in \mathbb{N}$.